Most dancers who compete in competitions and conferences attend dance studios. But each year, a small group of soloists choose to perform in an independent capacity, unaffiliated with a studio. There are many benefits to this approach, but there are also some possible drawbacks. Before signing up, think about what you’re willing to put into the experience and what you hope to gain.

Why independence?

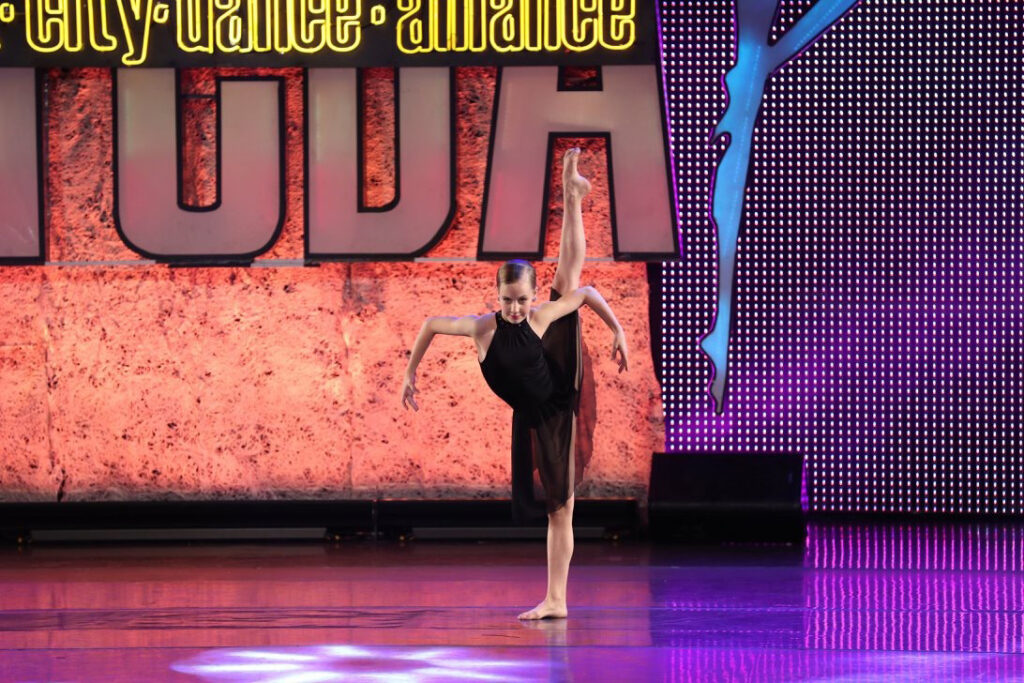

For dancers who don’t attend competition-oriented studios, independent competition may be the only option. As a ballet student, now in her first year as a principal member of the American Repertory Theater Ballet in Princeton, New Jersey, Rachel Quiner spends her weekdays in head-down mode and her weekends dancing with NUVO Convention and New York City Dance and other events alliance. Although Quina is able to compete with local dance studios, “many ballet dancers choose the independent route because their studios don’t host competitions and conferences,” she said. “While I’m focused on ballet, it’s been fun learning other styles and becoming more comfortable on stage.”

Even a studio Do When competing, it may only compete in one or two events per year, or only allow certain dancers to compete as soloists. “At my daughter’s studio, you had to be in 10th grade to get a solo dance opportunity,” said Mehgan Jarvie. Margaret trained primarily at the Lionville School of. Margaret competes in group competitions with her studio classmates, but also competes as an independent soloist in other competitions. “It was a self-esteem boost for her,” Jarvie said. “As a soloist, she can showcase her talent in a different way than in a group, and the feedback she gets will follow her back to the studio.”

What to consider

Being an independent competitor often means putting in more effort. Recital rehearsals may have to take place on your own time. Quina practiced solos in her family’s basement and received feedback from her family. Javi ensured that Margaret did not sign up for events that conflicted with Lineville’s competition schedule, and she and a rehearsal coach worked with her in the studio where Javi taught. Competing independently can also be costly. Considering hiring a choreographer? “Even a two-minute solo can be expensive!” warns Quina. She often asked her sisters (who were also dancers) to choreograph dances for her—or create her own. “I know how to highlight my strengths,” she points out. “Plus, when you choreograph your own solo, you can continually adjust it based on the judges’ feedback from one event to the next.”

That said, working independently with an outside choreographer can also lead to growth. Javi created competition solos for her daughter until last year, when she asked a colleague to choreograph them. The result was Margaret’s most successful season to date. “I think part of the reason she did so well was having a new person working with her,” Jarvie said.

Competing without studio support can feel lonely. As an independent competitor, you need to be willing to express yourself—even if you’re not naturally outgoing. “When you go up on stage to accept an award, you don’t have a bunch of friends cheering you on,” Jarvie points out. Getting to know conference faculty and other dancers can eliminate those feelings of isolation. It can also help you develop your networking skills, as making potential professional contacts is one of the key benefits of these events.

Working alone can give you a different perspective on dance because it requires you to understand your strengths and weaknesses. Even if one of your goals in competing as a solo soloist is to build confidence, “you have to know what you bring to the table,” Jarvie says. Building this kind of self-awareness can help you avoid falling into a common competitive trap: comparing yourself to those around you. “Be your own best dancer,” Javi said. “Dance for yourself.”