For the modest listener, a musician’s technical and interpretive performance skills are one of the most compelling reasons to purchase a concert ticket or a recording by that musician. But the humble critic has another, perhaps equally important, reason for investing time and money in a musician’s work. I like to call this skill “musical radar.” These talented musicians have the (sometimes uncanny) ability to choose their repertoire wisely.

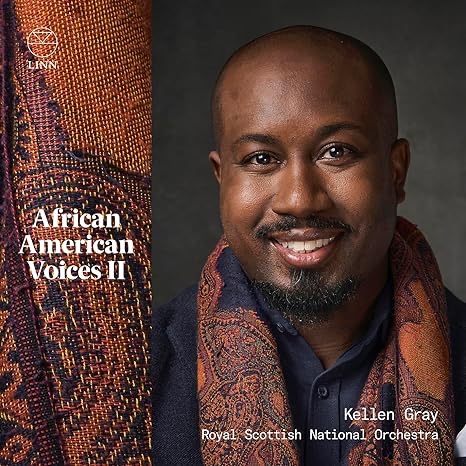

Conductor Karen Gray has a keen eye for the sound and meaning of music. Follow the likes of Leopold Stokowski (1882-1977), Dean Dixon (1915-1976), and Paul Freeman (1936-2015) Following in the conductor’s footsteps, Gray is clearly a champion of contemporary music and is now entering its second volume. Listeners are hoping for more substantial music releases by black composers whose works have been left unused for reasons that have nothing to do with quality.

Volume One includes masterpieces from the early to mid-twentieth century, such as William Levi Dawson’s 1934 Symphony of Negro Folk Songs, William Grant Still’s a symphony, “The American Negro” (1930) and George Walker’s “Lyric for Strings” (1946, orchestral 1990). These are undoubtedly great foundational works that deserve a place in the concert program, but these are works that have at least gained some exposure through recording. Nonetheless, they are still a good foundation upon which to build this series. Gray has a deep understanding of these works and his skills as a conductor are on good display here. But this is just the first wave of attacks in an exciting ongoing investigation.

In the second volume, we see more deeply the sensitivity of this conductor’s musical radar. These are new commercial recordings of mid-to-late 20th century orchestral works by black composers that have clear substance but remain unfairly ignored. It is from this “unusual” perspective that the enterprising conductor demonstrates his personal perspective and respect for musical history. They are inspiring. Hearing these authoritative performances will leave the listener wanting more, as we’ll hear some very exciting music that, if not a place in the repertoire, is at least worthy of consideration.

The record begins with Margaret Bonds’ “Montgomery Variations” (1964), a set of variations on the classic gospel tune, “I Want Jesus to Walk with Me.” But the work was “lost” and was only rediscovered in 2017. It was a hate crime that left four people dead. So this is the only surviving purely orchestral work by Bonds that gets a really good listen. What a great piece of work.

The works are composed of different parts with different titles (“Decision”, “Prayer Meeting”, “March”, “Dawn in Dixie”, “A Sunday in the South”, “Mourning”, “Blessing”). Each title is reflected in the musical mood of each section. This is a public and powerful condemnation of a horrific hate crime. Bonds’ work is sometimes harrowing, dark, and awe-inspiring, but the metaphorical quality of the music itself is also effective. It is also very close to an orchestral concerto, whose broad symphonic dimensions and clever orchestration are most deftly handled on this recording.

The “variation” genre is common in musical practice, but did not appear in the form of large-scale orchestral works until the late 19th century. Famous examples include Elgar’s “Riddle Variations”, Britten’s “Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Henry Purcell”, Brahms’ “Haydn Variations”, etc. Other works take their place in the concert hall together.

Next we introduce Ulysses Kay’s “Orchestral Concerto” (1948). The work was performed for the first time by the equally astute conductor Leopold Stokowski, who desperately needed a new recording, and Maestro Gray provided an educated and rich Insightful performances, like everything on this release, are a challenge for performers, broadcasters, and listeners not to let this music fade away. The “Orchestral Concerto” genre first appeared in Hindemith’s work of the same name in 1925, and the most famous work in this genre is undoubtedly Bartok’s 1943 “Orchestral Concerto.” The status of Kay’s work relative to other orchestral concertos remains to be seen/heard (just like Bonds’s), but at least there is now a chance to hear it in all its glory.

It is one of Kay’s major works and is of grand symphonic scale. This neoclassical work was written in 1948 and is divided into three movements. The work is very listenable, but it presents challenges for the orchestra, which this orchestra handled very well.

The disc ends with a rather brief work by a composer with whom even adventurous listeners (myself included) have limited familiarity. Coleridge Taylor-Parkinson. This is the only work here from the 21st century. This 2001 concert overture is subtitled “Worship,” reflecting Parkinson’s exposure to black church music, which he employed in this tonal poem written for large orchestra.

Gayle Murchison’s Beautiful Notes helps guide the listener by providing context and an accessible description of the composition process. This is an exciting release that builds well on the first volume and has listeners excitedly anticipating Karen Grey’s next installment.