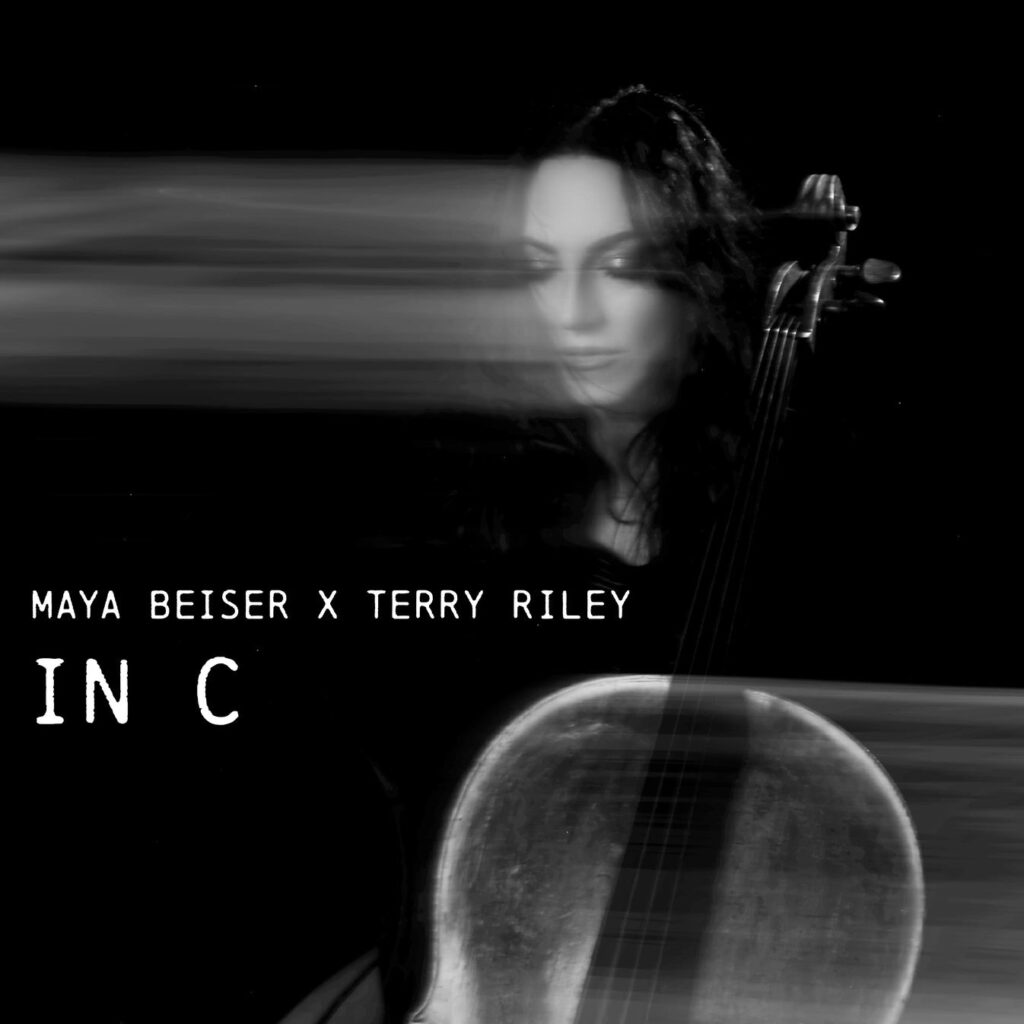

It is the performer’s responsibility to incorporate the nuances of their interpretive skills into their performance until they (and hopefully the composer and the audience) are satisfied that they have done justice to the music. When the music at hand challenges established norms and expectations, the task becomes quite daunting. One need only look at the numerous performances of Terry Riley’s seminal “In C” to realize that the nature and structure of the piece was designed to require experimentation with the instrumentation and with the music itself, which was composed by 51 Short notation composition.

Since its original release in 1968, at least 40 records have been released reflecting choices related to rhythm, instrumentation, and more. From “hairesis”, the Greek word for decision or choice). This kind of music requires smart choices.

This 1964 piece has been explicitly analyzed in Robert Carl’s excellent book Terry Riley’s in C, so interested readers should look to that book for explicit analytical details. My main point here is that music elicits choices more than traditional Western classical scores. The current version says almost as much about the performer/producer as it does about the composer. Of course, this is Maya Beiser’s expertise in the instrument. It was her performance experience at the center of the new music performance scene that gave her a clear grasp of the essential diversity of new music. In the end, it was the choices she dared to make that allowed her to become not just a performer, but actually a co-composer. All in an effort to please the composer and attract an adventurous audience. She did something similar on the Philip Glass album. She even did this while recording a Bach cello suite. Now that’s heresy at its best.

There could never be a definite recording of this work. This is an important part of the appeal of this music, and the importance of its challenge to the nature of Western classical music. The music itself is heretical.

Not all listeners will appreciate this new, innovative and deeply personal performance, but the composer shared an appreciative blurb on the album’s back cover, and the reviews I’ve seen have been uniformly positive.

Bessel’s use of harmony, and indeed the many extended functions of her instrument (plucked strings, harmonics, etc.), all contributed to her modifications of this music. On top of that, she even used her own voice and hired two percussionists to round out the arrangement of her piece.

Percussion emphasizes the ritualistic nature of the music. Harmony and polyphony place this version in the realm of the new music spectrum, even suggesting to the listener a Phil Spector “wall of sound,” another hallmark of some ritual music.

This is an album that requires repeated listening to appreciate the subtleties and insights of this interpretation. Here, even at her most transgressive, Besser does not seek to supplant other interpretations; instead, she simply demonstrates the power of this landmark work to inspire a new generation of talented performers (and enlightened listeners) , for that matter) experience the lasting cultural significance of this masterpiece. Awesome, Maya! Sincere thanks, Terry.

This is a “must have” recording.